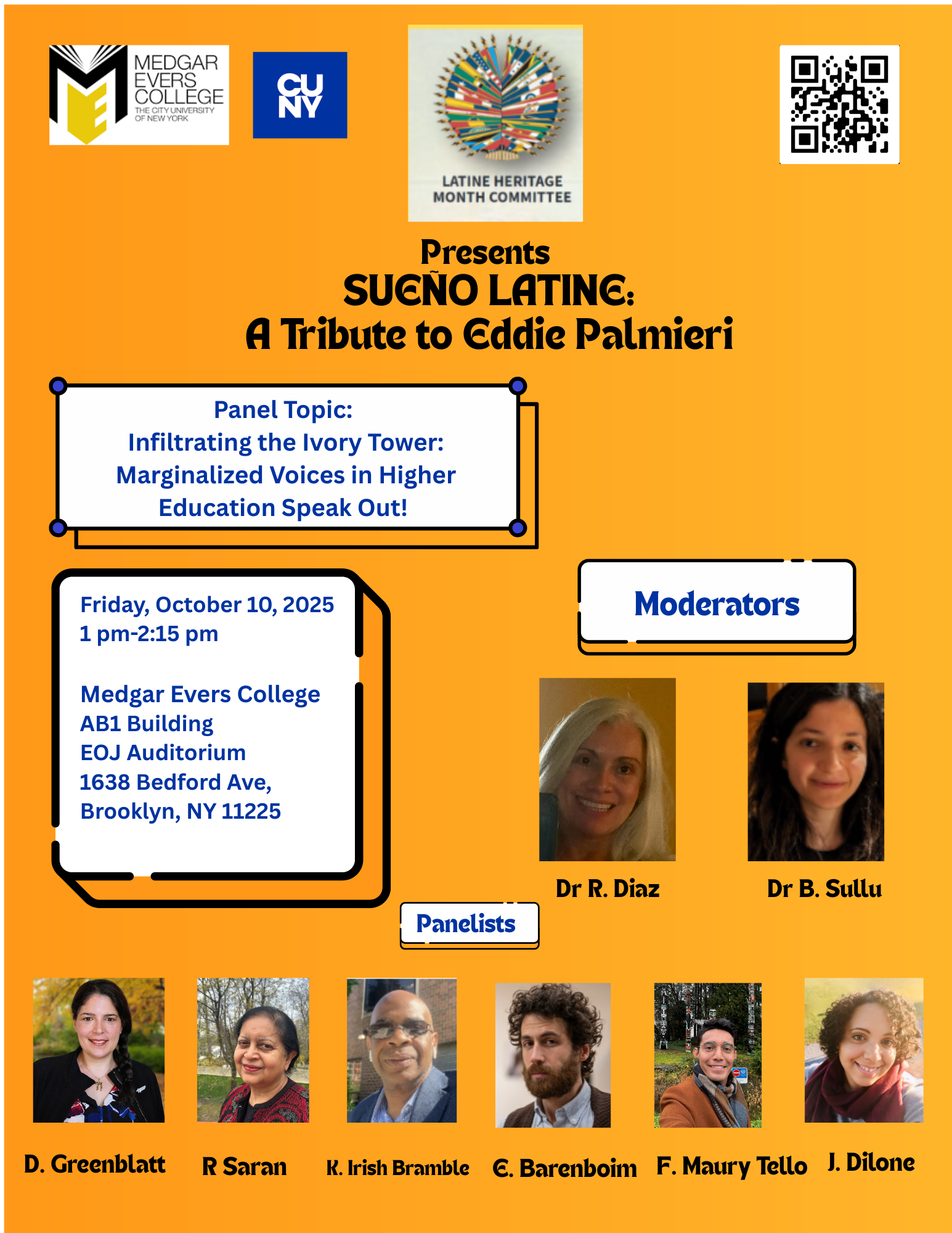

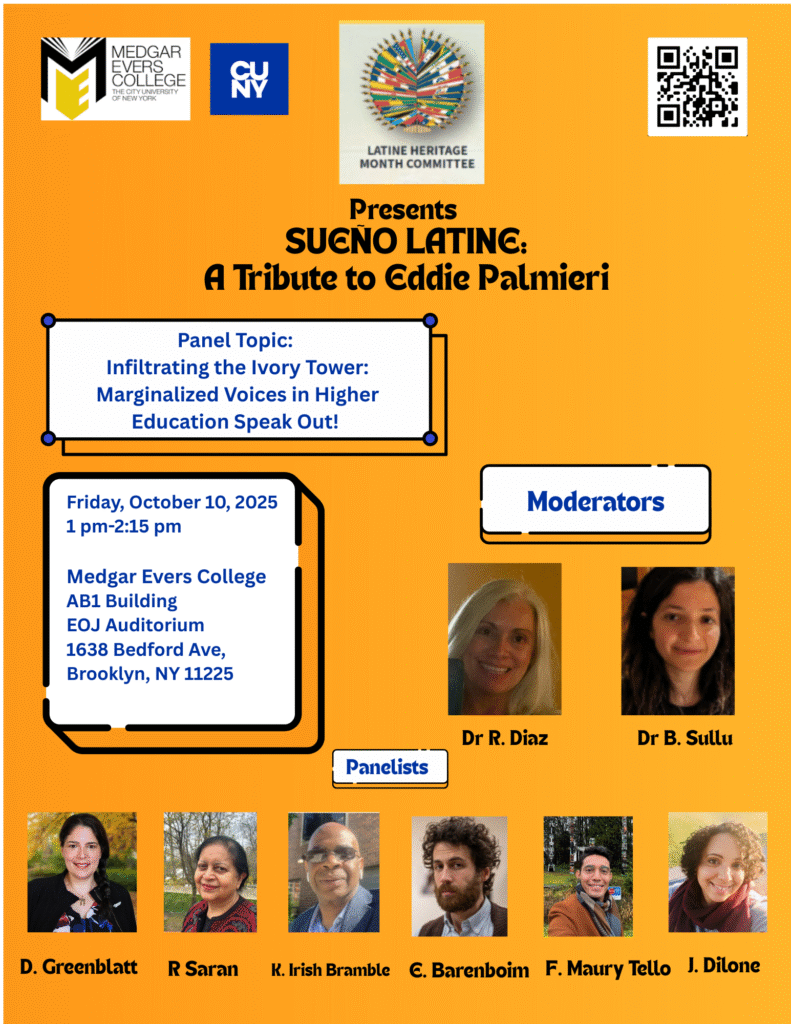

This panel will focus on the issue of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DEI) in Higher Education from Marginalized faculty of all backgrounds. This will be a spirited discussion, involving current issues in the socio-political arena, and how they impact the work we do as educators and scholars.

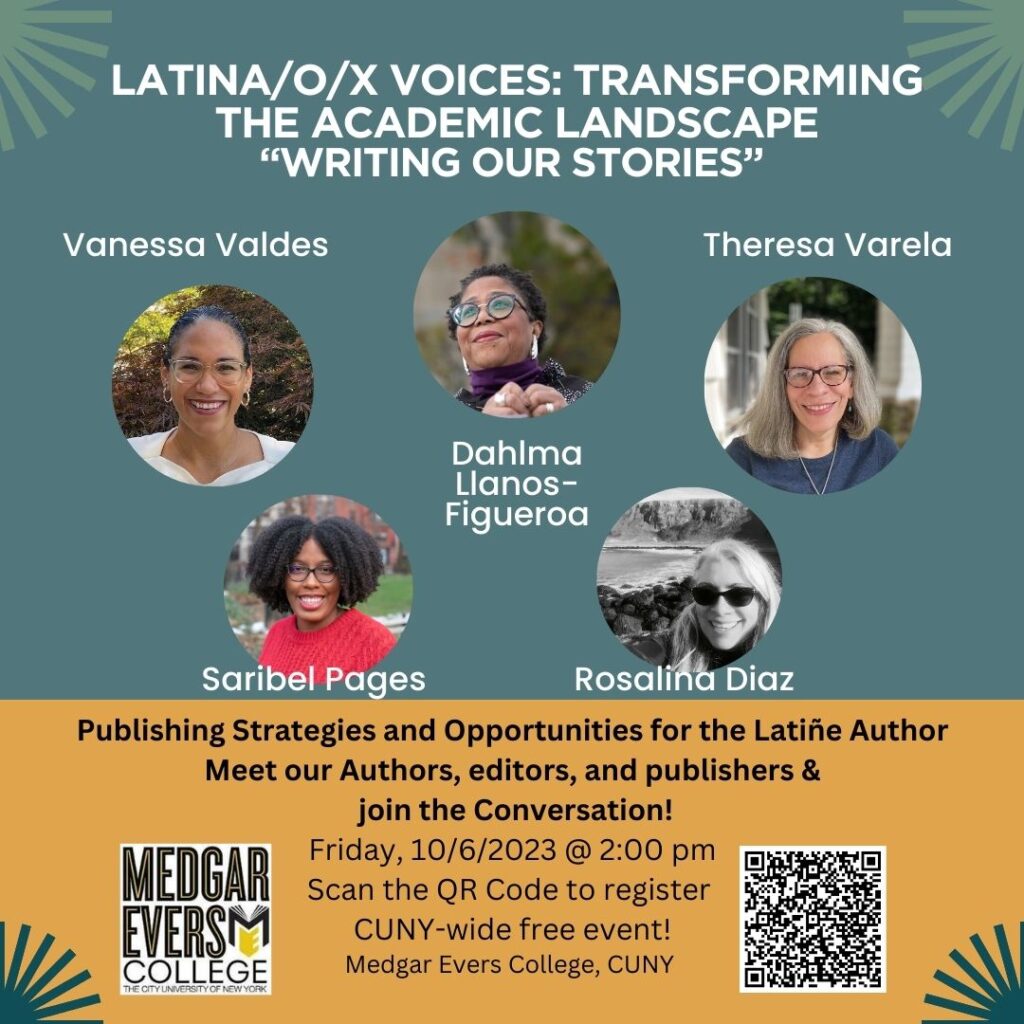

10/6/2023: Writing Our Stories: Publishing Strategies & Opportunities for the Latiñe Writer Medgar Evers College, CUNY

Decolonising paradise: The International Society of Ethnobiology conference in Kingston, Jamaica

Simon HoyteArticles, Indigenous peoples

I’ve just returned from the Society for Economic Botany & International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE) conference at the University of the West Indies, Kingston. Jamaica was not chosen for this conference arbitrarily. The island is a stark and visceral example of what ethnobiology can do.

The discipline of ethnobiology works “to understand and strengthen relationships between human societies and the natural world, and to promote biological, cultural, and linguistic diversity”. In short, it’s about human-nature relationships.

If you’re reading this from an apartment in Tottenham or Manhattan I suspect ‘human-nature relationships’ brings to mind city parks and going for a walk ‘in nature’ on weekends. However, for the Majority World (people living outside of urban bubbles in the Global North), relationships to nature are extraordinarily diverse. That’s why many ethnobiologists work with indigenous, local, and traditional peoples who retain many ways of relating to plants and animals which are not boxed in by dominant worldviews.

Being hosted in the Caribbean, the historical and contemporary injustices in relation to slavery and colonisation were front and centre.

One of the my favourite examples of this was presented by Rosalina Diaz. During September 2017, Hurricane Maria ripped through Puerto Rico and other Caribbean islands. Puerto Rico isn’t an independent country nor a U.S. state, it’s an ‘unincorporated U.S. territory’, and as such expected the U.S to assist the humanitarian effort after what was the worst natural disaster in recorded history in the region. Unfortunately, very little materialised and this changed the mentality of the island towards a sense of independence and self-sufficiency. Faced with a serious threat of strip mining by U.S. companies, a Puerto Rican community built up local support and institutional organisation to fend off the extraction, despite harassment from the U.S. Government. Instead, the community have the turned the land into a large forest area, restoring biodiversity, cultural connections to the land, social and health benefits, and reinstating their self-determination and resistance to imperialism.

Whilst ‘ethnobiology’ can at first appear academic and perhaps removed from our lives and struggles, I hope this post has revealed its relevance. The current calamity of the climate crisis, ecological collapse, and cultural destruction is all about the degradation of relationships between humans and other life. Homogenisation of these relationships through ongoing colonisation (e.g. this) to fit a dominant framework of land and resources as economic commodities has led to our current path, but we must not forget, and we must promote, the myriad of alternative relationships that human groups have to land and life which are far more healthy, reciprocal, and sustainable. As Sarah-Lan Mathez-Stiefel, the new president for the International Society for Ethnobiology, explained, ethnobiology is pivotal more than ever in forging new ways of relating to nature, in reinventing relationships. And all this is grounded in the recognition of multiple worldviews and knowledge systems.

Huge appreciation to Ina Vandebroek and David Picking for organising the conference, and the ExCiteS group for enabling my travel.

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement Nos. 694767 and ERC-2015-AdG)